Why Google Maps Doesn’t Work Properly in Asia And South Korea

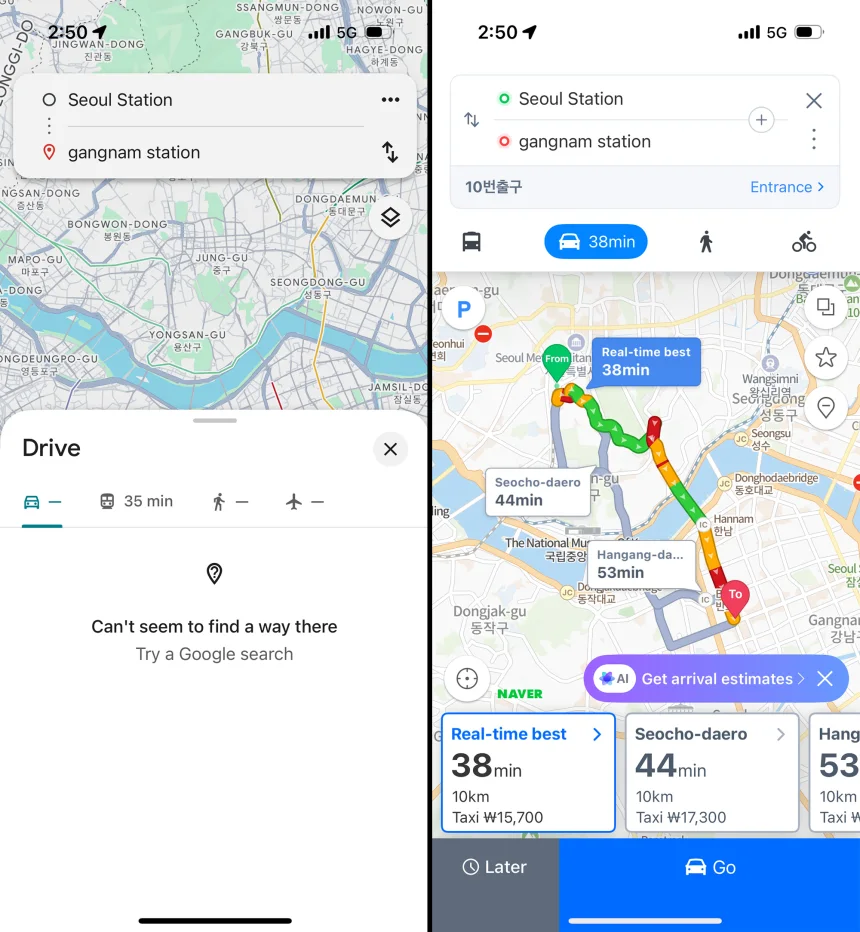

Despite being a global tech hub, South Korea restricts Google Maps from offering full navigation services like driving or walking directions. This forces visitors to rely on local apps such as Naver Map and Kakao Map.

The core issue is that Google cannot access South Korea’s detailed 1:5,000 scale map data, which is necessary for turn-by-turn navigation. Google has been requesting access since 2016, but the South Korean government has consistently denied these requests.

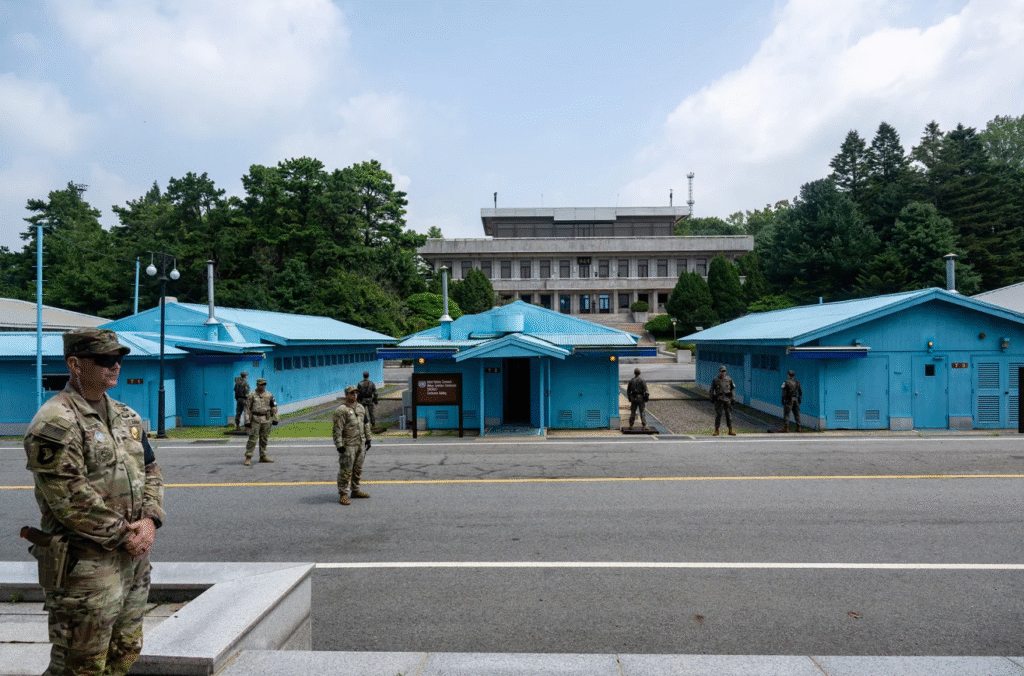

The official reason given is national security. Authorities argue that exporting detailed map data to foreign servers could reveal sensitive military and government sites, a concern heightened by the country’s proximity to North Korea. However, critics say these risks are exaggerated, especially since the same data is already used by domestic apps and satellite imagery is widely available from third-party providers.

Beyond security, broader issues are at play. South Korea is keen on maintaining digital sovereignty and supporting its domestic tech industry. Companies like Kakao and Naver have raised concerns that Google’s entry could dominate the market and threaten local businesses. Moreover, there’s little domestic pressure to approve Google’s request, as most South Koreans already rely on local apps, and the change would primarily benefit foreign tourists.

For tourists, this limitation can be frustrating. Language barriers and inconsistent English translations in Korean apps make them harder to use. Real-time walking directions and easy-to-search locations, standard in Google Maps elsewhere, are often unavailable.

A South Korean government council is expected to decide on Google’s latest request by October 2025. Most analysts expect another rejection unless Google offers significant security concessions or the South Korean government sees strategic value in approving it, especially amid ongoing trade negotiations with the United States.

This situation reflects a broader debate about data ownership, national interest, and the influence of global tech giants. As more countries assert control over their digital infrastructure, similar cases may emerge elsewhere in the world.